Where's my open smartphone?

The IBM Simon, released in 1994, has been called the first smartphone. But it was the launch of the iPhone in 2007 that brought touchscreen, pocket sized computers to the mass market. Today, over three quarters of adults in the UK own a smartphone. We keep our phones on 24/7, tiny computers running full operating systems, with microphones, cameras, GPS and accelerometers. The possibilities if we control them ourselves are amazing, and the possibilities if someone else gets control are terrifying. So we've got good reasons to want a phone running software that we can inspect and change.

This post, based on a talk I did for Portsmouth Linux User Group, looks at the landscape of free and open source software (FOSS) available for phones in late 2017.

The big two

Before we get into the FOSS alternatives, how open are the two platforms that make up the vast majority of the smartphone market today?

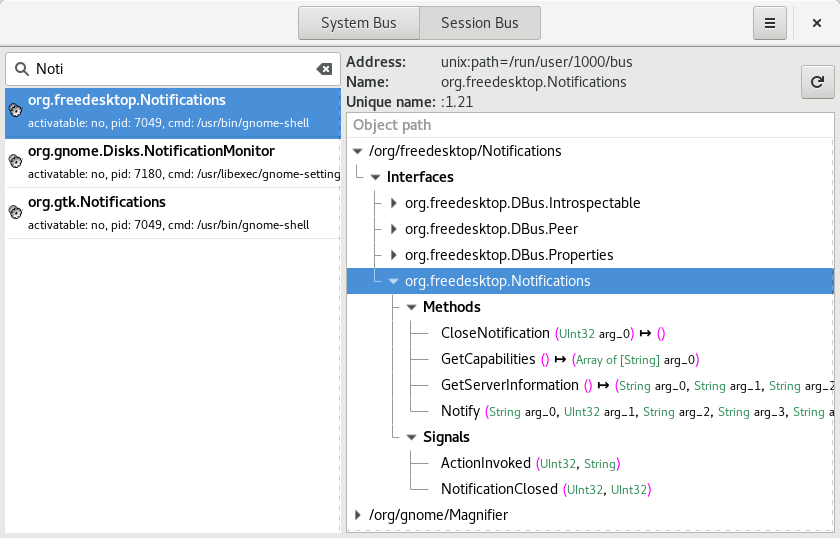

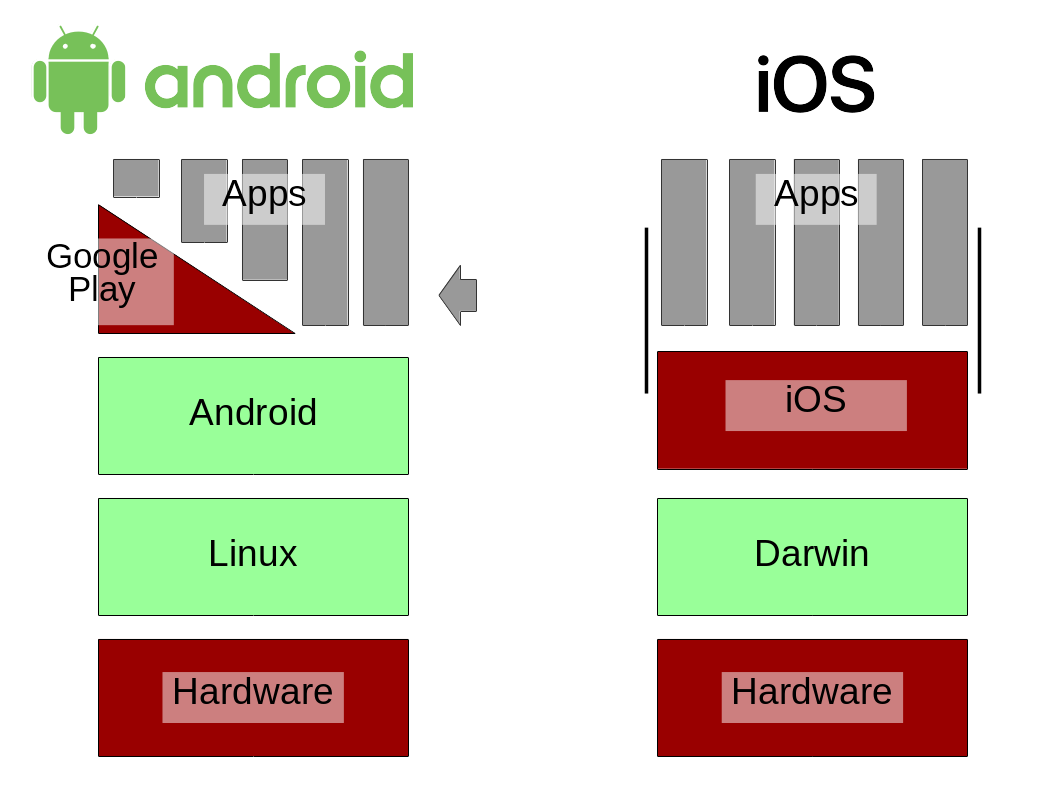

Open parts in green, proprietary parts in red.

Both Android and iOS have some open-source parts. But they require proprietary drivers and firmware to run on most phones. The freedom to modify the software and run your modified version is not readily available to end users. Google's Project Treble, which aims to make updating Android easier, might make it more feasible to run modified versions of Android.

Developers can build apps on the open source Android platform, but many apps also rely on proprietary Google APIs.

With an option in the security settings, Android allows 'sideloading' apps from sources other than the Google Play store. This possibility allows F-Droid to exist: an app store solely for FOSS applications. If you've got an Android device, give F-Droid a try: it's an easy, low risk step into the mobile open source world. Its catalogue of ~1400 applications is tiny compared to the millions in Google Play, but you might discover something interesting.

Now, what other options are there besides the big two?

Commercial offerings

First, what other platforms can you (or could you) buy a phone with?

Geeksphone Peak running Firefox OS. Image by Havarhen via Wikimedia Commons.

Firefox OS was launched in 2011, with a goal of running on inexpensive low-end smartphones, for people in developing countries who may not have a smartphone already. It relied heavily on browser technologies—HTML, CSS and Javascript—for both applications and the system UI. That's no surprise for a platform from Mozilla. A number of devices were released running Firefox OS, but in 2016 Mozilla decided to refocus its efforts elsewhere. A fork called KaiOS lives on, but there's little information available about it.

Nexus 5 running Ubuntu Touch. Image by Vinodh Moodley via Wikimedia Commons.

Ubuntu Touch was also launched in 2011. Spanish manufacturer BQ and Chinese Meizu made a handful of models running Ubuntu Touch. But it's best known for the Ubuntu Edge, a wildly ambitious crowdfunding campaign for a premium smartphone which could be plugged into a monitor and keyboard to run a full Ubuntu desktop. Despite thousands of eager pledges, it didn't get close to its $32 million goal, so people got their money back and the project was cancelled. Canonical kept promoting Ubuntu Touch until earlier this year, when they handed it over to the UBports community project.

Next up, there's... these things:

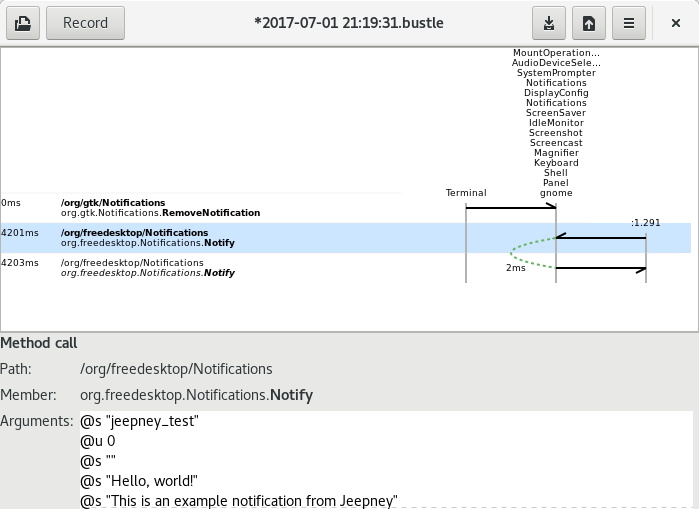

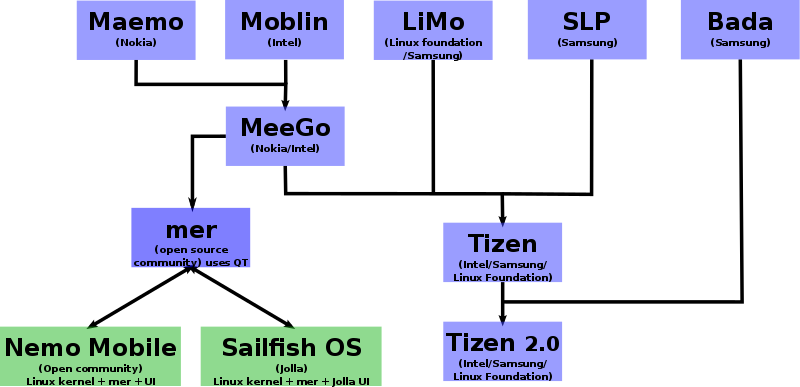

Mobile OS family tree, by Semsi Paco Virchow on Wikimedia Commons.

Nokia used to make remarkably open 'internet tablets' based on Maemo, and then one phone using Meego, before they went all-in on Windows Phone in 2011. We can only wonder what might have been if they'd stuck with their Linux platform.

Samsung's branch of this family is now called Tizen. Samsung have used it in several smartwatches, and a line of smartphones sold in India, such as the Z2. I'm not sure that Samsung is any better a guardian of a free and open platform than Google, but they might put a small dent in Android's market dominance.

Jolla smartphone running Sailfish OS. Image by Herman on Wikimedia Commons.

The other branch I want to point out is Sailfish, maintained by Jolla, a company founded by ex-Nokia employees. Jolla produced a couple of devices themselves, then turned to a licensing model. A few other companies have now released Sailfish phones. However, Sailfish OS is not completely open source; this Reddit post describes which parts of the stack are open.

DIY options

Nothing you can buy today could really be called an open smartphone, as far as I've found. So what can we install ourselves?

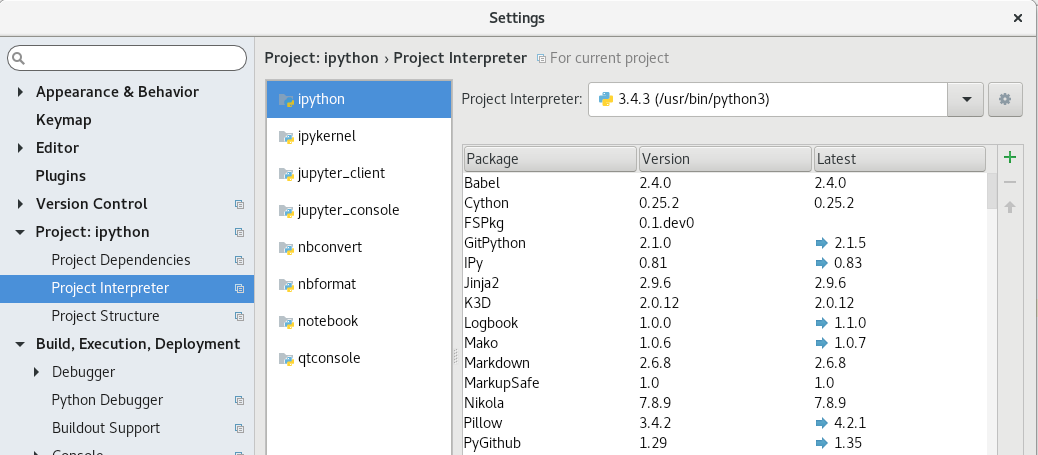

LineageOS, formerly called CyanogenMod, is probably the most popular alternative Android distribution. It has support for quite a lot of phones, but far from all of them. If you've got a supported phone, installation looks like this—not too complex, but you'd need quite a bit of confidence to try this on your only phone.

Android ROMs like Lineage are often used together with Open GApps, which provides the proprietary Google applications that are bundled into Android phones when you buy them. I'm not sure I'd call that 'open', but it's undeniably useful for many people who rely on Google services.

One other Android distribution I'll mention is Replicant. This is a strictly free software distribution, avoiding proprietary code as much as possible. However, it only supports a few devices, all of which appear to be older models. F-Droid's collection of open source apps (see above) is a crucial companion for a distribution like this.

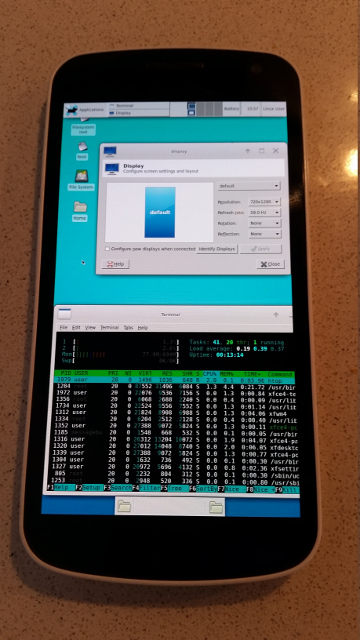

XFCE and Wayland running on a Galaxy Nexus. Image by Drebrez, via PostmarketOS wiki.

PostmarketOS is a new non-Android based entrant, which aims to keep devices running updated GNU/Linux for ten years. It can already run on more than 30 devices, which sounds impressive, but in most cases key features like audio and cameras are not working yet. We have to hope that this can evolve into a useful phone platform.

A new hope

I'm writing this a few weeks after the Purism Librem 5 crowdfunding campaign comfortably met its $1.5 million target. Purism, a company that already sells open laptops, plans to make a phone that's as open as possible, with hardware switches to disconnect parts like the cellular modem, which probably has to run proprietary code. They even say that, like the unrealised Ubuntu Edge, you will be able to plug in peripherals and run a full Linux desktop from it. The estimated shipping date is early in 2019.

The Librem 5 is currently the hot new thing in the open phone world, but there are already some concerns about it. At $600, it's priced like a premium device, but the proposed chips date from either 2013 or 2011, so the experience in 2019 may be underwhelming. And it could still require proprietary firmware for tasks like decoding video.

Key challenges

The biggest challenge for any alternative mobile OS is bootstrapping an app ecosystem. A platform with few apps struggles to attract users, and with few users there's little incentive for developers to make apps. Catch 22. Even Microsoft's efforts weren't enough to create a viable ecosystem around Windows Phone.

There are a couple of strategies companies have tried to avoid the 'app trap':

- HTML apps: the web is an open platform, and lots of services already have a mobile web interface, although it's often inferior to their native mobile apps. Despite all of the effort going into browsers, though, web applications still tend to feel slower than native ones, and rarely work well offline.

- Emulate Android: Sailfish does this, albeit with a proprietary component. But if you do it well, developers won't target your platform specifically, so it won't have much to differentiate it from Android.

Open source efforts face another challenge. The Fedora image I installed on my laptop would work on most 64-bit PCs, but with a phone OS, you have to download an image for one specific model. This makes it much harder to casually experiment with an alternative OS: someone needs to build it for the exact phone you have. PostmarketOS is attempting to change this model, but it's very early days. Meanwhile, Google's 'Project Treble' may provide a common interface to build a platform on, although it leaves a lot of code below the common interface under the control of vendors.

What options have I missed? Please point out other FOSS phone projects in the comments.